Here’s a full transcript of the interview with John Sculley on the subject of Steve Jobs.

It’s long but worth reading because there are some awesome insights into how Jobs does things.

It’s also one of the frankest CEO interviews you’ll ever read. Sculley talks openly about Jobs and Apple, admits it was a mistake to hire him to run the company and that he knows little about computers. It’s rare for anyone, never mind a big-time CEO, to make such frank assessment of their career in public.

UPDATE: Here’s an audio version of the entire interview made by reader Rick Mansfield using OS X’s text-to-speech system. It’s a bit robotic (Rick used the “Alex” voice, which he says is “more than tolerable to listen to”) but you might enjoy it while commuting or at the gym. The audio is 52 minutes long and it’s a 45MB download. It’s in .m4a format, which will play on any iPod/iPhone, etc.

Download it here (Option-Click the link; or right-click and choose “Save Linked File…”).

Q: You talk about the “Steve Jobs methodology.” What is Steve’s methodology?

Sculley: Let me give you a framework. The time that I first met Jobs, which was over 25 years ago, he was putting together the same first principles that I call the Steve Jobs methodology of how to build great products.

Steve from the moment I met him always loved beautiful products, especially hardware. He came to my house and he was fascinated because I had special hinges and locks designed for doors. I had studied as an industrial designer and the thing that connected Steve and me was industrial design. It wasn’t computing.

I didn’t know really anything about computers nor did any other people in the world at that time. This was at the beginning of the personal computer revolution, but we both believed in beautiful design and Steve in particular felt that you had to begin design from the vantage point of the experience of the user.

He always looked at things from the perspective of what was the user’s experience going to be? But unlike a lot of people in product marketing in those days, who would go out and do consumer testing, asking people, “What did they want?” Steve didn’t believe in that.

He said, “How can I possibly ask somebody what a graphics-based computer ought to be when they have no idea what a graphic based computer is? No one has ever seen one before.” He believed that showing someone a calculator, for example, would not give them any indication as to where the computer was going to go because it was just too big a leap.

Steve had this perspective that always started with the user’s experience; and that industrial design was an incredibly important part of that user impression. And he recruited me to Apple because he believed that the computer was eventually going to become a consumer product. That was an outrageous idea back in the early 1980’s because people thought that personal computers were just smaller versions of bigger computers. That’s how IBM looked at it.

Some of them thought it was more like a game machine because there were early game machines, which were very simple and played on televisions… But Steve was thinking about something entirely different. He felt that the computer was going to change the world and it it was going to become what he called “the bicycle for the mind.” It would enable individuals to have this incredible capability that they never dreamed of before. It was not about game machines. It was not about big computers getting smaller…

He was a person of huge vision. But he was also a person that believed in the precise detail of every step. He was methodical and careful about everything — a perfectionist to the end.

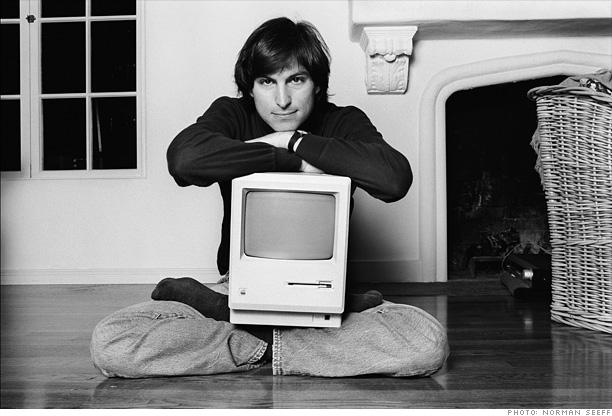

If you go back to the

Apple II, Steve was the first one to put a computer into a plastic case, which was called

ABS plastic in those days, and actually put the keyboard into the computer. It seems like a pretty simple idea today, looking back at it, but even at the time when he created the first Apple II, in 1977 — that was the beginning of the Jobs methodology. And it showed up in the Macintosh and showed up with his NeXT computer. And it showed up with the future Macs, the iMacs, the iPods and the iPhones.

What makes Steve’s methodology different from everyone else’s is that he always believed the most important decisions you make are not the things you do – but the things that you decide not to do. He’s a minimalist.

I remember going into Steve’s house and he had almost no furniture in it. He just had a picture of Einstein, whom he admired greatly, and he had a

Tiffany lamp and a chair and a bed. He just didn’t believe in having lots of things around but he was incredibly careful in what he selected. The same thing was true with Apple. Here’s someone who starts with the user experience, who believes that industrial design shouldn’t be compared to what other people were doing with technology products but it should be compared to people were doing with jewelry… Go back to my lock example, and hinges and a door with beautiful brass, finely machined, mechanical devices. And I think that reflects everything that I have ever seen that Steve has touched.

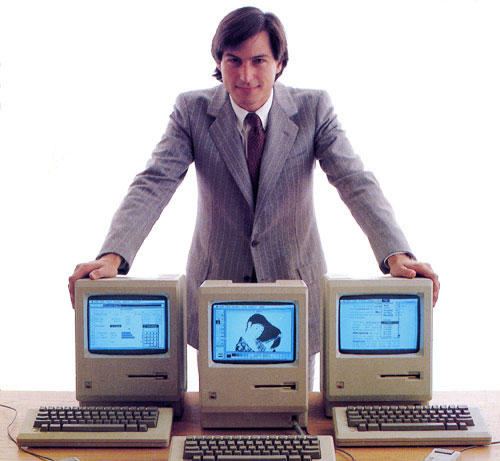

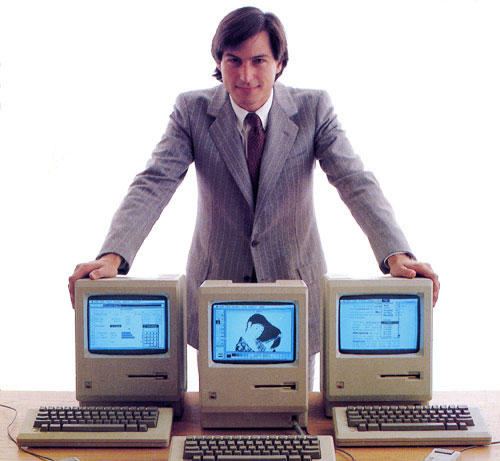

When I first saw the Macintosh — it was in the process of being created — it was basically just a series of components over what is called a bread board. It wasn’t anything, but Steve had this ability to reach out to find the absolute best, smartest people he felt were out there. He was extremely charismatic and extremely compelling in getting people to join up with him and he got people to believe in his visions even before the products existed. When I met the Mac team, which eventually got to 100 people but the time I met him it was much smaller, the average age was 22.

These were people who had clearly never built a commercial product before but they believed in Steve and they believed in his vision. He was able to work in multiple levels in parallel.

On one level he is working at the “change the world,” the big concept. At the other level he is working down at the details of what it takes to actually build a product and design the software, the hardware, the systems design and eventually the applications, the peripheral products that connect to it.

In each case, he always reached out for the very best people he could find in the field. And he personally did all the recruiting for his team. He never delegated that to anybody else.

The other thing about Steve was that he did not respect large organizations. He felt that they were bureaucratic and ineffective. He would basically call them “bozos.” That was his term for organizations that he didn’t respect.

The Mac team they were all in one building and they eventually got to one hundred people. Steve had a rule that there could never be more than one hundred people on the Mac team. So if you wanted to add someone you had to take someone out. And the thinking was a typical Steve Jobs observation: “I can’t remember more than a hundred first names so I only want to be around people that I know personally. So if it gets bigger than a hundred people, it will force us to go to a different organization structure where I can’t work that way. The way I like to work is where I touch everything.” Through the whole time I knew him at Apple that’s exactly how he ran his division.

Q: So how did he cope when Apple became bigger? I mean, Apple has tens of thousands of people now.

Sculley: Steve would say: “The organization can become bigger but not the Mac team. The Macintosh was set up as a product development division — and so Apple had a central sales organization, a central back office for all the administration, legal. It had a centralized manufacturing of that sort but the actual team that was building the product, and this is true for high tech products, it doesn’t take a lot of people to build a great product. Normally you will only see a handful of software engineers who are building an operating system. People think that it must be hundreds and hundreds working on an operating system. It really isn’t. It’s really just a small team of people. Think of it like the

atelier of an artist. It’s like an artist’s workshop and Steve is the master craftsman who walks around and looks at the work and makes judgments on it and in many cases his judgments were to reject something.

I can remember lots of evenings we would be there until 12 or 1 o’clock in the morning because the engineers usually don’t show up until lunchtime and they work well into the night. And an engineer would bring Steve in and show him the latest software code that he’s written. Steve would look at it and throw it back at him and say: “It’s just not good enough.” And he was constantly forcing people to raise their expectations of what they could do. So people were producing work that they never thought they were capable of. Largely because Steve would shift between being highly charismatic and motivating and getting them excited to feel like they are part of something insanely great. And on the other hand he would be almost merciless in terms of rejecting their work until he felt it had reached the level of perfection that was good enough to go into – in this case, the Macintosh.

Q: He was quite conscious about that, right? This was very well thought out, not just crazy capriciousness?

Sculley: No, Steve was incredibly methodical. He always had a white board in his office. He did not draw himself. He didn’t have particular drawing ability himself, yet he had an incredible taste.

The thing that separated Steve Jobs from other people like Bill Gates — Bill was brilliant too — but Bill was never interested in great taste. He was always interested in being able to dominate a market. He would put out whatever he had to put out there to own that space. Steve would never do that. Steve believed in perfection. Steve was willing to take extraordinary chances in trying new product areas but it was always from the vantage point of being a designer. So when I think about different kinds of CEOs — CEOs who are great leaders, CEOs who are great turnaround artists, great deal negotiators, great people motivators — but the great skill that Steve has is he’s a great designer. Everything at Apple can be best understood through the lens of designing.

Whether it’s designing the look and feel of the user experience, or the industrial design, or the system design and even things like how the boards were laid out. The boards had to be beautiful in Steve’s eyes when you looked at them, even though when he created the Macintosh he made it impossible for a consumer to get in the box because he didn’t want people tampering with anything.

In his level of perfection, everything had to be beautifully designed even if it wasn’t going to be seen by most people.

That went all the way through to the systems when he built the Macintosh factory. It was supposed to be the first automated factory but what it really was a final assembly and test factory with a

pick-to-pack robotic automation. It is not as novel today as it was 25 years ago, but I can remember when the CEO of General Motors along with

Ross Perot came out just to look at the

Macintosh factory. All we were doing was final assembly and test but it was done so beautifully. It was as well thought through in design as a factory, a lights out factory requiring many people as the products were.

Now if you leap forward and look at the products that Steve builds today, today the technology is far more capable of doing things, it can be miniaturized, it is commoditized, it is inexpensive. And Apple no longer builds any products. When I was there, people used to call Apple “a vertically-integrated advertising agency,” which was not a compliment.

Actually today, that’s what everybody is. That’s what HP is; that’s what Apple is; and that’s what most companies are because they outsource to EMS — electronics manufacturing services.

Q: Isn’t Nike a good analogy?

Sculley

Q: Isn’t Nike a good analogy?

Sculley: Yeah, probably, Nike is closer, I think that is true. I think if you look at the Japanese consumer electronics in that era they were all analog companies.

The one that Steve admired was Sony. We used to go visit Akio Morita and he had really the same kind of high-end standards that Steve did and respect for beautiful products. I remember Akio Morita gave Steve and me each one of the first

Sony Walkmans. None of us had ever seen anything like that before because there had never been a product like that. This is 25 years ago and Steve was fascinated by it. The first thing he did with his was take it apart and he looked at every single part. How the fit and finish was done, how it was built.

He was fascinated by the Sony factories. We went through them. They would have different people in different colored uniforms. Some would have red uniforms, some green, some blue, depending on what their functions were. It was all carefully thought out and the factories were spotless. Those things made a huge impression on him.

The Mac factory was exactly like that. They didn’t have colored uniforms, but it was every bit as elegant as the early Sony factories that we saw. Steve’s point of reference was Sony at the time. He really wanted to be Sony. He didn’t want to be IBM. He didn’t want to be Microsoft. He wanted to be Sony.

The challenge was in that era you couldn’t build digital products like Sony. Everything was analog and the Japanese companies approached things and you can read Prahalad’s book, from University of Michigan, he studied it. (Note: Sculley is referring to C.K. Prahalad’s “

Competing for the Future” (1994))

The Japanese always started with the market share of components first. So one would dominate, let’s say sensors and someone else would dominate memory and someone else hard drive and things of that sort. They would then build up their market strengths with components and then they would work towards the final product. That was fine with analog electronics where you are trying to focus on cost reduction — and whoever controlled the key component costs was at an advantage. It didn’t work at all for digital electronics because digital electronics you’re starting at the wrong end of the value chain. You are not starting with the components. You are starting with the user experience.

And you can see today the tremendous problem Sony has had for at least the last 15 years as the digital consumer electronics industry has emerged. They have been totally stove-piped in their organization. The software people don’t talk to the hardware people, who don’t talk to the component people, who don’t talk to the design people. They argue between their organizations and they are big and bureaucratic.

Sony should have had the iPod but they didn’t — it was Apple. The iPod is a perfect example of Steve’s methodology of starting with the user and looking at the entire end-to-end system.

It was always an end-to-end system with Steve. He was not a designer but a great systems thinker. That is something you don’t see with other companies. They tend to focus on their piece and outsource everything else.

If you look at the state of the iPod, the supply chain going all the way over to iPod city in China – it is as sophisticated as the design of the product itself. The same standards of perfection are just as challenging for the supply chain as they are for the user design. It is an entirely different way of looking at things.

Q: Where did he get the idea for controlling the whole widget? The idea to be in charge of everything, the whole system?

Sculley: Steve believed that if you opened the system up people would start to make little changes and those changes would be compromises in the experience and he would not be able to deliver the kind of experience that he wanted.

Q: But this control extends to every aspect of the product – even to opening the box. The experience of opening the box is designed by Steve Jobs.

Sculley: The original Mac really had no operating system. People keep saying, “Well why didn’t we license the operating system?” The simple answer is that there wasn’t one. It was all done with lots of tricks with hardware and software. Microprocessors in those days were so weak compared to what we had today. In order to do graphics on a screen you had to consume all of the power of the processor. Then you had to glue chips all around it to enable you to offload other functions. Then you had to put what are called “calls to ROM.” There were 400 calls to ROM, which were all the little subroutines that had to be offloaded into the ROM because there was no way you could run these in real time. All these things were neatly held together. It was totally remarkable that you could deliver a machine when you think the first processor on the Mac was less than three MIPs (Million Instructions Per Second), which today would be — I can’t think of any device which has three MIPS, or equivalent. Even your digital watch is at least 200 or 300 times more powerful than the first Macintosh. (NOTE. For comparison, today’s entry-level iMac uses an Intel Core i3 chip, rated at over 40,000 MIPS!)

It’s hard to conceive how he was able to accomplish so much with so little in those days. So for someone to build consumer products in the 1980s beyond what we did with the first Mac was literally impossible. In the 1990s with Moore’s Law and other things, the homogenization of technology, it became possible to begin to see what consumer products would look like but you couldn’t really build them. It really hasn’t been until the turn of the century that you sort of got the crossover between the cost of components, the commoditization and the miniaturization that you need for consumer products. The performance suddenly reached the point where you could actually build things that we can call digital consumer products. Because Steve’s design methodology was so correct even 25 years ago he was able to make a design methodology – his first principles — of user experience, focus on just a few things, look at the system, never compromise, compare yourself not to other electronic products but compare yourself to the finest pieces of jewelry — all those criteria — no one else was thinking about that. Everyone else was just going through an evolution of cheap products that are getting more powerful and cheaper to build. Like the MP3 player. Remember when he came in with the iPod, there were thousands of MP3 players out there. Can anyone else remember any of the others?

His tradeoff was he believed that he had to control the entire system. He made every decision. The boxes were locked.

Steve Jobs circa 1984. Illustration by Matthew Phelan

Q: But the motivation for this is the user experience?

Sculley: Absolutely. The user experience has to go through the whole end-to-end system, whether it’s desktop publishing or iTunes. It is all part of the end-to-end system. It is also the manufacturing. The supply chain. The marketing. The stores. I remember I was brought in because I had a design background and because I was a marketer. I had product marketing experience. Not because I knew anything about computers.

Q: I find that pretty fascinating. You say in your book that first and foremost you wanted to make Apple a “product marketing company.”

Sculley: Right. Steve and I spent months getting to know each other before I joined Apple. He had no exposure to marketing other than what he picked up on his own. This is sort of typical of Steve. When he knows something is going to be important he tries to absorb as much as he possibly can.

One of the things that fascinated him: I described to him that there’s not much difference between a Pepsi and a Coke, but we were outsold 9 to 1. Our job was to convince people that Pepsi was a big enough decision that they ought to pay attention to it, and eventually switch. We decided that we had to treat Pepsi like a necktie. In that era people cared what necktie they wore. The necktie said: “Here’s how I want you to see me.” So we have to make Pepsi like a nice necktie. When you are holding a Pepsi in your hand, its says, “Here’s how I want you to see me.”

We did some research and we discovered that when people were going to serve soft drinks to a friend in their home, if they had Coca Cola in the fridge, they would go out to the kitchen, open the fridge, take out the Coke bottle, bring it out, put it on the table and pour a glass in front of their guests.

If it was a Pepsi, they would go out in to the kitchen, take it out of the fridge, open it, and pour it in a glass in the kitchen, and only bring the glass out. The point was people were embarrassed to have someone know that they were serving Pepsi. Maybe they would think it was Coke because Coke had a better perception. It was a better necktie. Steve was fascinated by that.

We talked a lot about how perception leads reality and how if you are going to create a reality you have to be able to create the perception. We did it with something called the

Pepsi generation.

I had learned through a lecture that

Dr. Margaret Mead had given, an anthropologist in the 60’s, that the most important fact for marketers was going to be the emergence of an affluent middle class — what we call the

Baby Boomers, who are now turning 60. They were the first people to have discretionary income. They could go out and spend money for things other than what they had to have.

When we created Pepsi generation it was created with them in mind. It was always focusing on the user of the drink, never the drink.

Coke always focused on the drink. We focused on the person using it. We showed people riding dirt bikes, waterskiing, or kite flying, hang gliding — doing different things. And at the end of it there would always be a Pepsi as a reward. This all happened when color television was first coming in. We were the first company to do lifestyle marketing. The first and the longest-running lifestyle campaign was — and still is — Pepsi.

We did it was just as color television was coming in and when large-screen TVs were coming in, like 19-inch screens. We didn’t go to people who made TV commercials because they were making commercials for little tiny black-and-white screens. We went out to Hollywood and got the best movie directors and said we want you to make 60-second movies for us. They were lifestyle movies. The whole thing was to create the perception that Pepsi was number one because you couldn’t be number one unless you thought like number one. You had to appear like number one.

Steve loved those ideas. A lot of the stuff we were doing and our marketing was focused on when we bring the Mac to market. It has to be done at such a high level of perception of expectation that he will sort of tease people to want to find out what the product is capable of. The product couldn’t do very much in the beginning. Almost all of the technology was used for the user experience. In fact we did get a backlash where people said it’s a toy. It doesn’t do anything. But eventually it did as the technology got more powerful.

Q: Of course, Apple is famous for the same kind of lifestyle advertising now. It shows people living an enviable lifestyle, courtesy of Apple’s products. Hip young people grooving to iPods…

Sculley

Q: Of course, Apple is famous for the same kind of lifestyle advertising now. It shows people living an enviable lifestyle, courtesy of Apple’s products. Hip young people grooving to iPods…

Sculley. I don’t take any credit for it. What Steve’s brilliance is, is his ability to see something and then understand it and then figure out how to put into the context of his design methodology — everything is design.

An anecdotal story, a friend of mine was at meetings at Apple and Microsoft on the same day and this was in the last year, so this was recently. He went into the Apple meeting (he’s a vendor for Apple) and when he went into the meeting at Apple as soon as the designers walked in the room, everyone stopped talking because the designers are the most respected people in the organization. Everyone knows the designers speak for Steve because they have direct reporting to him. It is only at Apple where design reports directly to the CEO.

Later in the day he was at Microsoft. When he went into the Microsoft meeting, everybody was talking and then the meeting starts and no designers ever walk into the room. All the technical people are sitting there trying to add their ideas of what ought to be in the design. That’s a recipe for disaster.

Microsoft hires some of the smartest people in the world. They are known for their incredibly challenging test they put people through to get hired. It’s not an issue of people being smart and talented. It’s that design at Apple is at the highest level of the organization, led by Steve personally. Design at other companies is not there. It is buried down in the bureaucracy somewhere… In bureaucracies many people have the authority to say no, not the authority to say yes. So you end up with products with compromises. This goes back to Steve’s philosophy that the most important decisions are the things you decide NOT to do, not what you decide to do. It’s the minimalist thinking again.

Having been around in the early days, I don’t see any change in Steve’s first principles — except he’s gotten better and better at it.

Another example, which has been brilliant, is what he did with the retail stores.

He brought one of the top retailers in the world on his board to learn about retail (

Mickey Drexler from The Gap, who advised Jobs to build a prototype store before launch). Not only did he learn about retail, I’ve never been in a better store than an Apple store. It has the highest revenue per square foot of any store in the world but it’s not just the revenue, it’s the experience.

Apple stores are packed. You can go to the Sony center — go in the San Francisco center at the Moscone. There’s nobody there. You can go into the Nokia store, they have one in New York on 57th St. There’s nobody there.

But other people have the stores. They have the products to look at. You can touch and feel them but you walk into an Apple store and it’s just like an amazing experience. It is as much the people who are there shopping alongside you.

Again, it is like necktie products. It’s like being in an Apple store says, “here’s how I want you to see me. I’m here. I’m at the genius bar. I’m trying out the products. Look at me: I’m like the other people in the store.”

The user experience is taken all the way from the experience of using the product, to the advertising of how it is presented, to the design of the product. Steve is legendary for his fit and finish requirements on a product. Looking at the radius and parting lines and bezels and all these little details that designers pay attention to.

He will reject something which no one will see as a problem. But because his standards are so high, people sit there and say, “How does Apple do it? How does apple have such incredible products?”

I remember one of the things we talked about, Steve used to ask me: “How did Pepsi get such great advertising?” He asked if it was the agencies that you picked? And I said what it really is. First of all you have to have an exciting product and you have to be able to present it as an opportunity to do bold advertising.

But great advertising comes from great clients. The best creative people want to work for the best clients. If you are a client who doesn’t appreciate great work, or a client who won’t take risks and try new stuff, or a client who can’t get excited about the creative, then you’re the wrong kind of client.

Most big companies delegate it way down in the organization. The CEO rarely knows anything about the advertising except when it’s presented, when it’s all done. That’s not how we did it at Pepsi, not how we did it at Apple, and I’m sure it’s not how Steve does it now. He always adamantly involved in the advertising, the design and everything.

Q: Right. I hear Lee Clow flies up to Apple every week to meet with Jobs.

Sculley: Once you realize that Apple leads through design, than you can start to see, that’s what makes it different. Look at the stores, at the stairs in the stores. They are made of some special glass that had to be fabricated. And that’s so typical of the way he thinks. Everyone around him knows he beats to a different drummer. He sets standards that are entirely different than any other CEO would set.

He’s a minimalist and constantly reducing things to their simplest level. It’s not simplistic. It’s simplified. Steve is a systems designer. He simplifies complexity.

If you are someone who doesn’t care about it, you end up with simplistic results. It’s amazing to me how many companies make that mistake. Take the

Microsoft Zune. I remember going to

CES when Microsoft launched Zune and it was literally so boring that people didn‘t even go over to look at it… The Zunes were just dead. It was like someone had just put aging vegetables into a supermarket. Nobody wanted to go near it. I’m sure they were very bright people but it’s just built from a different philosophy. The legendary statement about Microsoft, which is mostly true, is that they get it right the third time. Microsoft’s philosophy is to get it out there and fix it later. Steve would never do that. He doesn’t get anything out there until it is perfected.

Q

: Let’s talk about advertising, which is so important to Apple. In you book you talk about ‘strategic advertising’ – advertising as strategy. That’s a very interesting idea…

Sculley

Q

: Let’s talk about advertising, which is so important to Apple. In you book you talk about ‘strategic advertising’ – advertising as strategy. That’s a very interesting idea…

Sculley: At the time I came to Silicon Valley there was no advertising… The only one who was really interested in doing advertising was Apple. H-P didn’t advertise in those days. No one advertised in those days on a big brand basis. One of the things that I was recruited to Apple to help do was to bring big brand advertising to Apple.

…

The Apple logo was multicolor because the Apple II was the first color computer. No one else could do color, so that’s why they put the color blocks into the logo. If you wanted to print the logo in a magazine ad or on a package you could print it with four colors but Steve being Steve insisted on six colors. So whenever the Apple logo was printed, it was always printed in six colors. It added another 30 to 40 percent to the cost of everything, but that’s what Steve wanted. That’s what we always did. He was a perfectionist even from the early days.

Q: That drives some people a little bit crazy. Did it drive you crazy?

Sculley: It’s okay to be driven a little crazy by someone who is so consistently right. What I’ve learned in high tech is that there’s a very, very thin line between success and failure. It’s an industry where you are constantly taking risks, particularly if you’re a company like Apple, which is constantly living out on the edge.

Your chance of being on one side of that line or the other side of the line is about equal. Sometimes… he was wrong tactically on a number of things. He wouldn’t put a hard drive in the Macintosh. When someone asked him about communications, he just threw a little disk across the room and said, “That’s all we’ll ever need.” On the other hand, Steve led the development of what was called AppleTalk and AppleLink. AppleTalk was the communications that enabled the Macintosh to communicate to the laser printer that enabled… desktop publishing.

AppleTalk was brilliant in its day. It was as brilliant as the Macintosh. It was another example of using a minimalist approach and solving a problem that no one else thought was a problem that needed to be solved. Steve was solving problems back in the 80s that turned out 15, 20 years later to be exactly the right problems to be working on. The challenge was we were decades away from when the technology would be homogenized enough and powerful enough to be able to make all those things mass market. He was just, in many cases, he was way ahead of his time.

Looking back, it was a big mistake that I was ever hired as CEO. I was not the first choice that Steve wanted to be the CEO. He was the first choice, but the board wasn’t prepared to make him CEO when he was 25, 26 years old.

They exhausted all of the obvious high-tech candidates to be CEO… Ultimately, David Rockefeller, who was a shareholder in Apple, said let’s try a different industry and let’s go to the top head hunter in the United States who isn’t in high tech: Gerry Roche.

They went and recruited me. I came in not knowing anything about computers. The idea was that Steve and I were going to work as partners. He would be the technical person and I would be the marketing person.

The reason why I said it was a mistake to have hired me as CEO was Steve always wanted to be CEO. It would have been much more honest if the board had said, “Let’s figure out a way for him to be CEO. You could focus on the stuff that you bring and he focuses on the stuff he brings.”

Remember, he was the chairman of the board, the largest shareholder and he ran the Macintosh division, so he was above me and below me. It was a little bit of a façade and my guess is that we never would have had the breakup if the board had done a better job of thinking through not just how do we get a CEO to come and join the company that Steve will approve of, but how do we make sure that we create a situation where this thing is going to be successful over time?

My sense is that when Steve left (in 1986, after the board rejected his bid to replace Sculley as CEO) I still didn’t know very much about computers.

My decision was first to fix the company, but I didn’t know how to fix companies and to get it back to be successful again.

All the stuff we did then were all his ideas. I understood his methodology. We never changed it. So we didn’t license the products. We focused on industrial design. We actually built up our own in-house design organization, which they have to this day. We developed the PowerBook… We developed QuickTime. All these things were built around Steve’s philosophy… It was all about sales and marketing and the evolution of the products.

All the design ideas were clearly Steve’s. The one who should really be given credit for all that stuff while I was there is really Steve.

I made two really dumb mistakes that I really regret because I think they would have made a difference to Apple. One was when we are at the end of the life of the Motorola processor… we took two of our best technologists and put them on a team to go look and recommend what we ought to do.

They came back and they said it doesn’t make any difference which

RISC architecture you pick, just pick the one that you think you can get the best business deal with. But don’t use

CISC. CISC is complex instructions set. RISC is reduced instruction set.

So Intel lobbied heavily to get us to stay with them… (but) we went with IBM and Motorola with the PowerPC. And that was a terrible decision in hindsight. If we could have worked with Intel, we would have gotten onto a more commoditized component platform for Apple, which would have made a huge difference for Apple during the 1990s. In the 1990s, the processors were getting powerful enough that you could run all of your technology and software, and that’s when Microsoft took off with their Windows 3.1.

Prior to that you had to do it in software and hardware, the way Apple did. When the processors became powerful enough, it just became a commodity and the software can handle all those subroutines we had to do in hardware.

So we totally missed the boat. Intel would spend 11 billion dollars and evolve the Intel processor to do graphics… and it was a terrible technical decision. I wasn’t technically qualified, unfortunately, so I went along with the recommendation.

The other even bigger failure on my part was if I had thought about it better I should have gone back to Steve.

I wanted to leave Apple. At the end of 10 years, I didn’t want to stay any longer. I wanted to go back to the east coast. I told the board I wanted to leave and IBM was trying to recruit me at the time. They asked me to stay. I stayed and then they later fired me. I really didn’t want to be there any longer.

The board decided that we ought to sell Apple. So I was given the assignment to go off and try to sell Apple in 1993. So I went off and tried to sell it to AT&T to IBM and other people. We couldn’t get anyone who wanted to buy it. They thought it was just too high risk because Microsoft and Intel were doing well then. But if I had any sense, I would have said: “Why don’t we go back to the guy who created the whole thing and understands it. Why don’t we go back and hire Steve to come back and run the company?”

It’s so obvious looking back now that that would have been the right thing to do. We didn’t do it, so I blame myself for that one. It would have saved Apple this near-death experience they had.

One of the issues that got me fired was that there was a split inside the company as to what the company ought to do. There was one contingent that wanted Apple to be more of a business computer company. They wanted to open up the architecture and license it. There was another contingent, which I was a part of, that wanted to take the Apple methodology — the user experience and stuff like that — and move into the next generation of products, like the Newton.

But the Newton failed. It was a new direction. It was so fundamentally different. The result was I got fired and they had two more CEOs who both licensed the technology but… they shut down the industrial design. They turned out computers that looked like everybody else’s computers and they no longer cared about advertising, public relations. They just obliterated everything. We’re just going to become an engineering type company and they almost drove the company into bankruptcy during that.

I’m actually convinced that if Steve hadn’t come back when he did — if they had waited another six months — Apple would have been history. It would have been gone, absolutely gone.

What did he do? He turned it right back to where it was — as though he never left. He went all the way back.

So during my era, really everything we did was following his philosophy — his design methodology.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t as good at it as he was. Timing in life is everything. It just wasn’t a time when you could build consumer products and he wasn’t having any more luck at

NeXT than we were having at Apple — and he was better at it than we were. The one thing he did do better: he built the better next-generation operating system, which eventually was merged into Apple’s operating system.

Q: People say he killed the Newton – your pet project – out of revenge. Do you think he did it for revenge?

Sculley

Q: People say he killed the Newton – your pet project – out of revenge. Do you think he did it for revenge?

Sculley: Probably. He won’t talk to me, so I don’t know.

The Newton was a terrific idea, but it was too far ahead of its time. The Newton actually saved Apple from going bankrupt. Most people don’t realize in order to build Newton, we had to build a new generation microprocessor. We joined together with

Olivetti and a man named

Herman Hauser, who had started Acorn computer over in the U.K. out of Cambridge university. And Herman designed the ARM processor, and Apple and Olivetti funded it. Apple and Olivetti owned 47 percent of the company and Herman owned the rest. It was designed around Newton, around a world where small miniaturized devices with lots of graphics, intensive subroutines and all of that sort of stuff… when Apple got into desperate financial situation, it sold its interest in ARM for $800 million. If it had kept it, the company went on to become an $8 or $10 billion company. It’s worth a lot more today. That’s what gave Apple the cash to stay alive.

So while Newton failed as a product, and probably burnt through $100 million, it more than made it up with the ARM processor… It’s in all the products today, including Apple’s products like the iPod and iPhone. It’s the Intel of its day.

Apple is not really a technology company. Apple is really a design company. If you look at the iPod, you will see that many of the technologies that are in the iPod are ones that Apple bought from other people and put together. Even when Apple created Macintosh, all the ideas came out of Xerox and Apple recruited some of the key people out of Xerox.

Everything Apple does fails the first time because it is out on the bleeding edge. Lisa failed before the Mac. The Macintosh laptop failed before the PowerBook. It was not unusual for products to fail. The mistake we made with the Newton was we over-hyped the advertising. We hyped the expectation of what the product could actually, so it became a celebrated failure.

Q: I want to ask about Jobs’ heroes. You say Edwin Land was one of his heroes?

Sculley: Yeah, I remember when Steve and I went to meet Dr Land. Dr Land had been kicked out of Polaroid. He had his own lab on the Charles River in Cambridge. It was a fascinating afternoon because we were sitting in this big conference room with an empty table. Dr Land and Steve were both looking at the center of the table the whole time they were talking. Dr Land was saying: “I could see what the

Polaroid camera should be. It was just as real to me as if it was sitting in front of me before I had ever built one.”

And Steve said: “Yeah, that’s exactly the way I saw the Macintosh.” He said if I asked someone who had only used a personal calculator what a Macintosh should be like they couldn’t have told me. There was no way to do consumer research on it so I had to go and create it and then show it to people and say now what do you think?

Both of them had this ability to not invent products, but discover products. Both of them said these products have always existed – it’s just that no one has ever seen them before. We were the ones who discovered them. The Polaroid camera always existed and the Macintosh always existed — it’s a matter of discovery. Steve had huge admiration for Dr. Land. He was fascinated by that trip.

Q: What other heroes did he talk about?

Sculley: He became very close with Ross Perot.

Ross Perot came and visited Apple several times and visited the Macintosh factory. Ross was a systems thinker. He created EDS (Electronic Data Systems) and was an entrepreneur. He believed in big ideas; change the world ideas. He was another one.

Akio Morita was clearly one of his great heroes. He was an entrepreneur who built Sony and did it with great products — Steve is a products person.

Q: How about Hewlett-Packard? Jobs has said in the early days that HP was a big influence when he worked there briefly with Woz.

Sculley: HP was not a model for Apple. I’ve never heard that. HP had the “HP way,” where Bill Hewitt and David Packard would wander people would leave their work out on their desk at night and they’d wonder around and look at it. So it was very open and it was an engineers company. Apple is a designers company, not an engineers company. HP was never in those days known for great design. It was known for great engineering, not great design. No, I don’t remember HP being a model for Apple at all.

Q: Didn’t Jobs also manage by walking around?

Sculley: He did that. Everyone did that in Silicon Valley. That was what HP contributed to the way Silicon Valley does business. There are certain characteristics that all Silicon Valley startups have and that’s one of them. That clearly came from HP. HP was the father of the walking around style of management. And HP was the father of the engineer being at the top of the hierarchy in companies.

Engineers are far more important than managers at Apple — and designers are at the top of the hierarchy. Even when you look at software, the best designers like Bill Atkinson, Andy Hertzfeld, Steve Capps, were called software designers, not software engineers because they were designing in software. It wasn’t just that their code worked. It had to be beautiful code. People would go in and admire it. It’s like a writer. People would look at someone’s style. They would look at their code writing style and they were considered just beautiful geniuses at the way they wrote code or the way they designed hardware.

Q: Steve Jobs is famous for being a student of design. He’d run around looking intently at all the Mercedes in the Apple car park.

Sculley: Steve was a fanatic on looking at how things were printed: the fonts, the colors, the layouts. I remember once after Steve had left, one of our tasks was to go and build the business in Japan. Apple had a $4 million of turnover and we were being sued by the Japanese FTC and people saying we ought to close the office down — it’s losing money. I remember going over and to make a long story short, four years later we were a $2 billion dollar business and the number two company in Japan selling computers.

A big part of it was that we had to learn to make products the way the Japanese wanted products. We were assembling products in Singapore and sending them to Japan. And the first thing the customer saw when they opened the box was the manual, but the manual was turned the wrong way around – and the whole batch was rejected. In the United States, we’d never experienced anything like that. If you put the manual in this way or that way — what difference did it make?

Well, it made a huge difference in Japan. Their standards are just different than ours. If you look at Apple and the attention to detail. The “open me first,” the way the box is designed, the fold lines, the quality of paper, the printing — Apple just goes to extraordinary lengths. It looks like you are buying something from Bulgari or one of the highest in jewelry firms. At the time, it was the Japanese.

We used to study Italian designers when we were looking for selecting a design company before we selected

Hartmut Esslinger from Frog to do what was called

the Snow White design. We were looking at Italian car designers. We really did study the designs of cars that they had done and looking at the fit and finish and the materials and the colors and all of that. At that time, nobody was doing this in Silicon Valley. It was the furthest thing on the planet from Silicon Valley back then in the 80’s. Again, this is not my idea. I could relate to it because of my interest and background in design, but it was totally driven by Steve.

At the time when Steve was gone and I took over I was highly criticized. They said, “How could they put a guy who knows nothing about computers in charge of a computer company?” What a lot of people didn’t realize was that Apple wasn’t just about computers. It was about designing products and designing marketing and it was about positioning.

People used to call us a “vertically-integrated advertising agency” and that was a huge cheap shot. Engineers couldn’t think of anything worse to say about a company than to say it was a “vertically-integrated advertising agency.” Well, guess what? They all are today. That’s the model. The supply chain is managed somewhere else.

http://www.cultofmac.com/63295/john-sculley-on-steve-jobs-the-full-interview-transcript/#bWUgkH1ppomdPMzJ.99